Equality: America

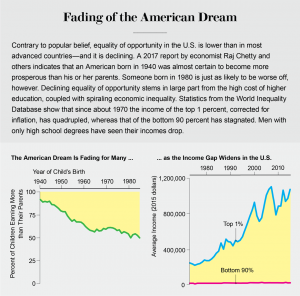

Contrary to popular belief, equality of opportunity in the U.S. is lower than in most advanced countries -- and it is declining. A 2017 report by economist Raj Chetty and others indicates than an American born in 1940 was almost certain to become more prosperous than his or her parents. Someone born in 1980 is just as likely to be worse off, however. Declining equality of opportunity stems in large part from the high costs of higher education, coupled with spiraling economic inequality. Statistics from the World Inequality Database shows that since about 10970 the income of the top 1 percent, corrected for inflation, has quadrupled, whereas that of the bottom 90 percent has stagnated. Men with only high school degrees have seen their incomes drop.

An alternative theory is far more consonant with the facts. Since the mid-1970s the rules of the economic game have been rewritten, both globally and nationally, in ways that advantage the rich and disadvantage the rest. And they have been rewritten further in this perverse direction in the U.S. than in other developed countries—even though the rules in the U.S. were already less favorable to workers. From this perspective, increasing inequality is a matter of choice: a consequence of our policies, laws and regulations.

In the U.S., the market power of large corporations, which was greater than in most other advanced countries to begin with, has increased even more than elsewhere. On the other hand, the market power of workers, which started out less than in most other advanced countries, has fallen further than elsewhere. This is not only because of the shift to a service-sector economy—it is because of the rigged rules of the game, rules set in a political system that is itself rigged through gerrymandering, voter suppression and the influence of money. A vicious spiral has formed: economic inequality translates into political inequality, which leads to rules that favor the wealthy, which in turn reinforces economic inequality.

Political inequality, in its turn, gives rise to more economic inequality as the rich use their political power to shape the rules of the game in ways that favor them—for instance, by softening antitrust laws and weakening unions

An account of how the rules have been shaped must begin with antitrust laws, first enacted 128 years ago in the U.S. to prevent the agglomeration of market power. Their enforcement has weakened—at a time when, if anything, the laws themselves should have been strengthened.

Network effects: you are far more likely to join a particular social network or use a certain word processor if everyone you know is already using it.

The cost of making an additional e-book or photo-editing program is essentially zero.

In short, entry is hard and risky, which gives established firms with deep war chests enormous power to crush competitors and ultimately raise prices. Making matters worse, U.S. firms have been innovative not only in the products they make but in thinking of ways to extend and amplify their market power.

Rigged rules also explain why the impact of globalization may have been worse in the U.S. A concerted attack on unions has almost halved the fraction of unionized workers in the nation, to about 11 percent. (In Scandinavia, it is roughly 70 percent.) Weaker unions provide workers less protection against the efforts of firms to drive down wages or worsen working conditions.

Moreover, U.S. investment treaties such as the North Atlantic Free Trade Agreement—treaties that were sold as a way of preventing foreign countries from discriminating against American firms—also protect investors against a tightening of environmental and health regulations abroad. For instance, they enable corporations to sue nations in private international arbitration panels for passing laws that protect citizens and the environment but threaten the multinational company's bottom line.

Weak corporate governance laws have allowed chief executives in the U.S. to compensate themselves 361 times more than the average worker, far more than in other developed countries. Financial liberalization—the stripping away of regulations designed to prevent the financial sector from imposing harms, such as the 2008 economic crisis, on the rest of society—has enabled the finance industry to grow in size and profitability and has increased its opportunities to exploit everyone else. Banks routinely indulge in practices that are legal but should not be, such as imposing usurious interest rates on borrowers or exorbitant fees on merchants for credit and debit cards and creating securities that are designed to fail. They also frequently do things that are illegal, including market manipulation and insider trading. In all of this, the financial sector has moved money away from ordinary Americans to rich bankers and the banks' shareholders.

a legal provision enacted in 2003 prohibited the government from negotiating drug prices for Medicare—a gift of some $50 billion a year or more to the pharmaceutical industry

Special favors, such as extractive industries' obtaining public resources such as oil at below fair-market value or banks' getting funds from the Federal Reserve at near-zero interest rates (which they relend at high interest rates), also amount to rent extraction. Further exacerbating inequality is favorable tax treatment for the rich. In the U.S., those at the top pay a smaller fraction of their income in taxes than those who are much poorer—a form of largesse that the Trump administration has just worsened with the 2017 tax bill.

Solution

There is no magic bullet to remedy a problem as deep-rooted as America's inequality. Its origins are largely political, so it is hard to imagine meaningful change without a concerted effort to take money out of politics—through, for instance, campaign finance reform. Blocking the revolving doors by which regulators and other government officials come from and return to the same industries they regulate and work with is also essential.

Recent research, such as work done by Jonathan Ostry and others at the International Monetary Fund, suggests that economies with greater equality perform better, with higher growth, better average standards of living and greater stability. Inequality in the extremes observed in the U.S. and in the manner generated there actually damages the economy.

Moreover, because the rich typically spend a smaller fraction of their income on consumption than the poor, total or “aggregate” demand in countries with higher inequality is weaker. Societies could make up for this gap by increasing government spending—on infrastructure, education and health, for instance, all of which are investments necessary for long-term growth.

- We need more progressive taxation and high-quality federally funded public education, including affordable access to universities for all, no ruinous loans required.

- We need modern competition laws to deal with the problems posed by 21st-century market power and stronger enforcement of the laws we do have.

- We need labor laws that protect workers and their rights to unionize. We need corporate governance laws that curb exorbitant salaries bestowed on chief executives, and we need stronger financial regulations that will prevent banks from engaging in the exploitative practices that have become their hallmark. We need better enforcement of antidiscrimination laws: it is unconscionable that women and minorities get paid a mere fraction of what their white male counterparts receive.

- We also need more sensible inheritance laws that will reduce the intergenerational transmission of advantage and disadvantage.

- We need to guarantee access to health care. We need to strengthen and reform retirement programs, which have put an increasing burden of risk management on workers (who are expected to manage their portfolios to guard simultaneously against the risks of inflation and market collapse) and opened them up to exploitation by our financial sector (which sells them products designed to maximize bank fees rather than retirement security).

- Our mortgage system was our Achilles' heel, and we have not really fixed it. With such a large fraction of Americans living in cities, we have to have urban housing policies that ensure affordable housing for all.

Source

Joseph E. Stiglitz is a University Professor at Columbia University and Chief Economist at the Roosevelt Institute. He received the Nobel prize in economics in 2001. Stiglitz chaired the Council of Economic Advisers from 1995–1997, during the Clinton administration, and served as the chief economist and senior vice president of the World Bank from 1997–2000. He chaired the United Nations commission on reforms of the international financial system in 2008–2009. His latest authored book is Globalization and Its Discontents Revisited (2017).

[1]